Name: Laurie A. Williams

Hometown: Bentonville, Arkansas

Current City: New Orleans

Occupation: Tutor, creator and founder of Louisiana Poetry Project, educator

Age: 52

What does poetry mean to you?

Poetry means survival of humanity. When I used to teach middle school, I would ask my students to come up with a definition for poetry and each student would work on an individual definition. Then we would work on a class definition together from our various individual definitions. I still do this activity sometimes when I work with teachers in hopes of getting them to include more poetry in their classes, to not be afraid of poetry, and to expand their definition and understanding of poetry. I remember the first year I did this with my students, they asked me for my definition. Of course, I wasn't prepared with an answer, so I thought about it for several minutes before telling them that the best way I could define it was that poetry is the breaking of your sternum to set your heart free. I'm still not sure if it was the best idea to say that to thirty seventh graders at Catholic school, but that is the definition that stays with me and still seems most accurate to me. Poetry is deeply personal, but is also connects us with one another and lets us know that we are not alone. Poetry makes sense of the chaos while still recognizing the chaos.

Favorite poem or poet:

My favorite poem/poet changes from day to day. I have poets and poems I go back time and time again. During hurricane Katrina, these lines from Yeats ran through my head as a constant mantra: "The best lack all conviction, while the worst/ are full of passionate intensity." This segment from Octavio Paz's "Fable" (Eliot Weinberger's translation) is a second skin, or maybe a tattoo etched into my bones.—

There was only one huge word with no back to it

A word like the sun

One day it broke into tiny pieces

They were the words of the language we now speak

Pieces that will never come together

Broken mirrors where the world sees itself shattered

Right now, my favorite poet is Pinkie Gordon Lane. She is often my go-to poet when the news weighs heavy. I found her in my research for the Louisiana Poetry Project. She was Louisiana Poet Laureate from 1989-1992. I had never read her work in any of my classes or come across it through any of my poet friends and acquaintances. Her last book, Elegy for Etheridge, sits on my desk with a pale pink, wrinkled and ragged sticky note marking the page to the right-hand side of "Sexual Privacy of Women on Welfare." I put the sticky note there last November (2016). Early Wednesday morning, November 9th, this poem popped into my head. I couldn't remember which one of her books it was in or the exact title, but I could see it sitting on the page, and I remembered the second strophe and the last line verbatim. So I pulled all of her books off the shelf, and thumbed through them until I found this poem:

Sexual Privacy of Women on Welfare

The ACLU Mountain States Regional Office came across a welfare application used in [a certain state] for women with illegitimate children.

Among the questions:

--When and where did you first meet the defendant [the child's father].

--When and where did intercourse first occur.

--Frequency and period of time during which intercourse occurred.

--Was anyone else ever present. If yes, give dates, names, and addresses.

--Were preventative measures always used.

--Have you had intercourse with anyone other than the defendant.

--If yes, give dates, names, and addresses.

--The Privacy Report, American Civil Liberties Union Foundation, vol 4, no 3, Oct. 1976

When and where did you first

confront loneliness?

When and where did you resist

the urge to die?

Did you pull a blind around

your sorrow?

Was anyone present? If yes, give

names and dates and addresses.

Did you survive?

Were preventative measures always

used?

Who listens to the rage of your

silent screams? Give the frequency

and period of time,

dates and names and addresses . . .

Will you promise never to breathe ice?

To follow the outline

of a city street whose perspective

darkens with the morning light?

Document.

Pinkie Gordon Lane

from her book Elegy for Etheridge

Why do you like this poem?

I love how Pinkie responds to news and information in her poems, how she takes dehumanizing information and humanizes it. I usually prefer my news with a little satire or parody to temper it, to give that temporary anesthesia of the heart that comedy provides, allowing for clarity and distance. But with Pinkie's poems, she pulls you in closer--the subject of the poem and the speaker sit in the room with you. The second strophe arrests my breath each time I read it. The final line--"Document" as a verb and not a noun goes through my head in a continuous cycle these days. As I read and watch the news, as I interact with colleagues and students, as I research, as I daydream, that imperative sentence from this poem demands I pay more attention and make note of what I think, feel, say, know, and understand.

How do you approach poetry with your students?

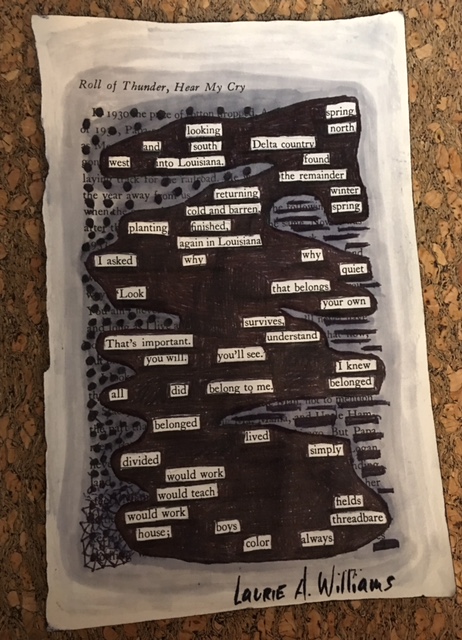

One of my favorite projects to do with my students is a found poem or a black out poem because it makes them think about words and language in an entirely different way. I always use a page from a book we are reading as a class. They have to let go of having the words they choose have the same meaning as the author originally intended. They have to redefine what writing is and how meaning occurs.

A blackout home, as seen in Mildred D. Taylor's Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry, created by Laurie A. Williams